JIM RAVES ABOUT MANHATTAN EDIT WORKSHOP'S 70'S NYC EDITING LEGENDS PANEL

/By Jim Hession, 2013 Fellow

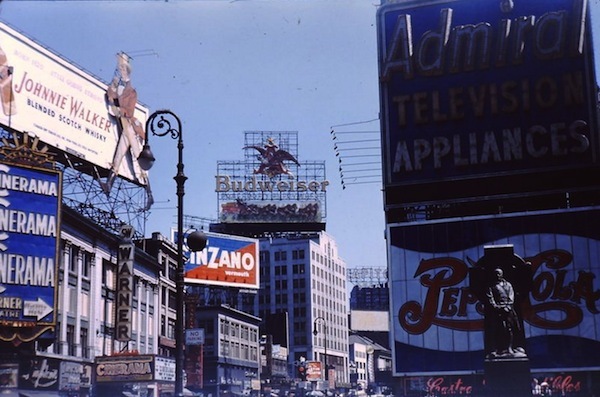

Scary. Soiled. Scandalous. And basically shitty. This is how history not-so fondly remembers New York City of the 1970s. Drug use was rampant all across town; employment was not. Crime rates soared; faith in America’s greatest city plummeted. Bryant Park was referred to as “Needle Park,” and the 6 Train was appropriately termed “Mugger’s Express,” a place where armed bandits were known to have jumped turnstiles in a quest to rob hapless straphangers for free. Sorry kids, “Dave and Busters” and “TGI Fridays” were most definitely not the names of wholesome corporate establishments residing in Times Square, although such monikers likely echo those of the pimps and prostitutes (respectively) who once worked its corners. And when the financially devastated city teetered on bankruptcy in 1975, the nation’s president famously told New York to “drop dead.”

At the same time, on the opposite side of the country, the quaint town of Hollywood was suffering from its own version of social turmoil, as the mighty studio structure, which had long reigned supreme over American cinema for nearly four decades, started to crack. Existing on the heels of the 1960s Revolution(s) and operating amidst the economic recession of the ’70s, classical Hollywood studios and their traditional products never really stood a chance in America’s new era. Consequently, the late ’60s and ’70s marked the emergence of a new wave in cinema history, one in which a breed of young, fresh and relevant filmmakers broke free from the conventional modes of cinematic storytelling and started making movies that were, well, very different than the ones that mass audiences had grown accustomed to. Their films were a little more real, a little grittier, and a lot less comforting. Think: not-Casablanca and more-Taxi Driver (or, Bonnie and Clyde, Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid, Easy Rider, A Clockwork Orange, Deliverance, The Godfather, American Graffiti, Badlands,The Exorcist, Lenny, Chinatown, Apocalypse Now …).

It should come as no surprise to anyone, therefore, that out of the muck and mire that plagued New York City sprang glorious contributions to this new cinematic renaissance. Of the directors who rose to prominence in the 1970s, many were New Yorkers, including Sidney Lumet, Martin Scorsese, Woody Allen, Arthur Penn, Brian De Palma, and Bob Fosse. Not too shabby.

And for sure, the individual successes of New York’s directors were due in no small part to the bourgeoning community of cinematographers, sound mixers and editors who were beginning to take root in Manhattan. This specialized community was very talented. It was very small. And most of all, it was centralized. In fact, most every major motion picture that came out of New York at the time passed through one of three physical locations in and around Times Square: the old Studebaker Building at 1600 Broadway, the famed Brill Building at 1619 Broadway, or around the corner at 254 West 54th Street (the same building that housed the famed nightclub Studio 54). In the 1970s, New York City became a hub of innovative filmmaking. A tiny hub. But a significant one, nonetheless.

Taking a break from the symposium: Manhattan Edit Workshop's Jason Banke & Josh Apter, Fellow Jim Hession, and KSFEF's Rachel Shuman and Garret Savage.

All of this historic backstory brings me to a recent panel discussion that I was lucky enough to attend thanks to the generosity and support of the Manhattan Edit Workshop, which hosted a day-long symposium entitled, "Inside the Cutting Room: Sight, Sound and Story." The event was chock-full of inspiring and insightful seminars, and a fabulous summary of the day’s happenings can be found here. In short, all of it was awesome!

But the discussion that most captivated me was the day’s keynote event, which was moderated by film historian Bobbie O’Steen and included legendary editors Alan Heim, A.C.E., Jerry Greenberg, A.C.E., Susan Morse, A.C.E., and Bill Pankow, A.C.E. Wow! The panel was fittingly called, ”NY Legends of the ’70s: Master Editors Discuss Their Work From This Revolutionary Era in American Cinema.”

I am a relatively young editor who belongs to one of the first generations of film editors that, ironically, has never been contractually obligated to even touch a piece of physical celluloid film. Thanks to computers and the software applications Avid and Final Cut Pro, I have never known what it feels like to actually cut and connect the A-Side of a piece of film to the B-Side of a piece of film while using my God-given fingers (and a razor blade, I suppose). In discussing my own work, I frequently talk about “making cuts,” but in reality, I’ve never actually cut a physical piece of film. Never. Ever. Not once.

And so, I struggle to aptly express my genuine euphoria for the opportunity to have heard from the panel’s Editing Greats, all of whom laboriously spliced and cut actual film on the old Moviolas and Flatbed editing machines, collectively creating the very cinematic works that were seminally influential in my own personal love affair with the art of filmmaking. Additionally, as someone who was born on the island of Manhattan in January of 1981, I could not help but feel that these editors somehow represent a period in New York City’s illustrious history that I never had the chance to experience firsthand. As the title of the program states, the esteemed panelists are, indeed, living “NY Legends” who once discovered hope within the borders of a city that didn’t have enough of it.

Without any more further ado, here are seven of my favorite clips from the discussion:

CLIP ONE: JERRY WORKS THE ROOM

In this clip, Jerry opens up the talk with a couple of priceless zingers that immediately win over the crowd. Two noteworthy facts: 1. the panel discussion was held mere days after the NSA internet surveillance story had first hit the headlines, and 2. Jerry obviously got a kick out of being referred to as a “Legend.”

CLIP TWO: JERRY FONDLY REMEMBERS HIS FIRST ASSISTANT EDITING GIG

Before going on to edit such classics as The French Connection, Kramer vs. Kramer and Apocalypse Now, Jerry worked as an assistant for the legendary editor Dede Allen (Bonnie and Clyde,Slaughterhouse-Five, Dog Day Afternoon, The Breakfast Club). Here, Jerry reminisces about his first day on the job in Dede’s cutting room at 1600 Broadway. The Studebaker Building has since been torn down and predictably replaced by upscale condominiums.

CLIP THREE: SUSAN RECOUNTS A STORY THAT FORESHADOWS HER BRILLIANT CONTRIBUTIONS TO THE WORLD OF FILMMAKING

Attention all over-worked, under-utilized assistant editors: no matter what the task, there is always a chance to show off the genius that lurks behind your embarrassing paycheck. In this story, Susan remembers how she first caught the eye of Dede Allen (yes, the same Dede that Jerry worked for) while filling in as a production assistant for a director on a low-budget PBS production that was being cut at 254 West 54th Street. Shortly after the recounted incident, Susan went on to edit Woody Allen’s Manhattan, which was nominated for two Academy Awards.

CLIP FOUR: BILL EXPRESSES HIS AMAZEMENT WITH THE OPPORTUNITY TO WORK AS JERRY’S ASSISTANT ON KRAMER vs. KRAMER (NOTE: JERRY IS SITTING DIRECTLY NEXT TO HIM)

Fair warning: there’s another Dede Allen mention coming up. No wonder that she’s remembered as being such a remarkable editor and wonderful human being! When viewing this clip, it is important to keep in mind that Bill and Jerry went on to become co-editors and fellow collaborators on films such as Scarface and The Untouchables. And again, the two close friends are sitting directly next to each other.

CLIP FIVE: ALAN RECALLS A FORMATIVE “MINI-LESSON” THAT HE RECEIVED FROM DIRECTOR AND EDITOR ARAM AVAKIAN WHILE WORKING AS A YOUNG SOUND EFFECTS EDITOR ON SIDNEY LUMET’S THE GROUP.

Here, Alan discovers the beauty that can be found in “the movement of food.” Spoken like a true editor …

CLIP SIX: ALAN ILLUSTRATES WHY THE JOB OF AN EDITOR OFTEN REQUIRES MORE SKILLS THAN “JUST” EDITING

Ok, the following clip demands a decent amount of set-up and explanation. But trust me, it’s worth it. Alan edited a film called, All That Jazz. For his efforts, he was awarded with an Academy Award for Best Editing in 1979. Bob Fosse, who Alan considers to be a dear friend and long-time collaborator, directed the film. The main character of All That Jazz is named Joe Gideon, a troubled theatre director who also doubles as a Hollywood movie director. By all accounts, the character is closely based on the life of the film’s director, Bob Fosse. So far, so good? One more thing: Alan (the editor on the panel) also made a cameo appearance in the film as an actor. He played the role of (you guessed it) a film editor. Enjoy.

CLIP SEVEN: JERRY REVEALS THE SECRET OF NEW YORK’S MANY CONTRIBUTIONS TO THIS REVOLUTIONARY ERA IN AMERICAN CINEMA

One word: community.

As I walked home from this remarkable discussion to my apartment located on the west side of midtown Manhattan (mere blocks from the site of so many of the stories that I had just heard), I was most struck by the fact that none of the famed editors on the panel had seemed particularly interested in discussing the practice of actual editing, per se. Certainly, I reckoned, all of them possess profoundly relevant techniques and approaches and theories and philosophies concerning filmmaking’s most unsung craft. They are legends, after all!

But what is clear to me is that the things that ended up mattering the most to these long-time film editors have little to do with specific editorial decisions and the thinking behind them; instead, these four masters are much more inclined to recall the personal relationships that they forged over the course of creating their many films while also reflecting upon how their respective professional endeavors ended up enriching their own personal lives. In other words, it’s not about the specific edits. It’s about the environment in which the edits stemmed from. And what they collectively resulted in.

For me, an ambitious young editor still hoping to prove his worth, these truths are both pertinent and inspiring, because at the end of the day, I try my best to always remember that the opportunity to pursue a line of work that one genuinely loves is a luxury not afforded to most people. Consequently, if I am ever lucky enough to be able to bang out a respectable livelihood in this crazy business, I will forever consider myself to be an extremely fortunate human being. Alan, Jerry, Susan and Bill helped remind of this conviction.

And one day, I hope to have a story that is as symbolic and compelling as the one about Jerry discovering his “sign” out the window of Dede Allen’s cutting room. If not? I suppose that I’ll just have to settle for the joy of remembering his tale each time I throw back a glass of Johnnie Walker on the rocks.

Bottoms up!